Investing in the 1970s

by Rob Stoll, CFP®, CFA Financial Advisor & Chief Financial Officer / November 9, 2022

Investors have endured a rapidly shifting investment landscape over the last 12 months. As we head into 2023, we see scope for inflation to come down and for the Federal Reserve to pause its interest rate hiking cycle. But does that mean we go back to the old ways of investing that we had become accustomed to the last 25 years? Probably not. We think the next 10 years will look more like investing in the 1970s, when investors struggled to out-pace inflation. What’s going to change, and how can investors navigate that environment?

Investing Difficulty in 2022 Has been Historic

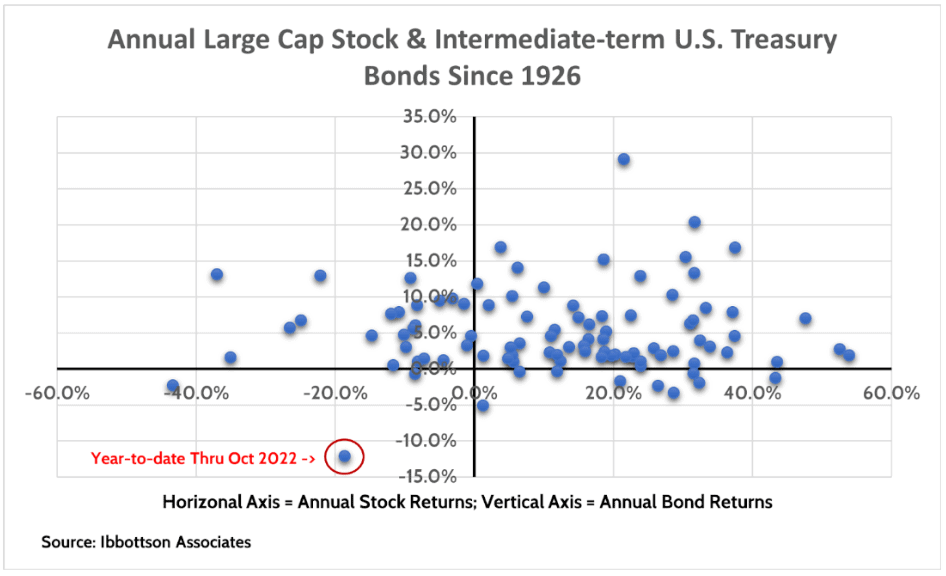

The difficult investment environment in 2022 has been historic. We all know that. Stocks have flirted with bear market territory this year while bonds are suffering one of their worst years ever. The scatter plot chart below plots stock and bond returns since 1926. It shows that 2022 is only the third year to record lower stock and government bond prices in the same year.

Ideally, we always want to be in the upper right-hand quadrant; it represents stocks and bonds rising together. That’s the environment that has prevailed over much of the last 30 years.

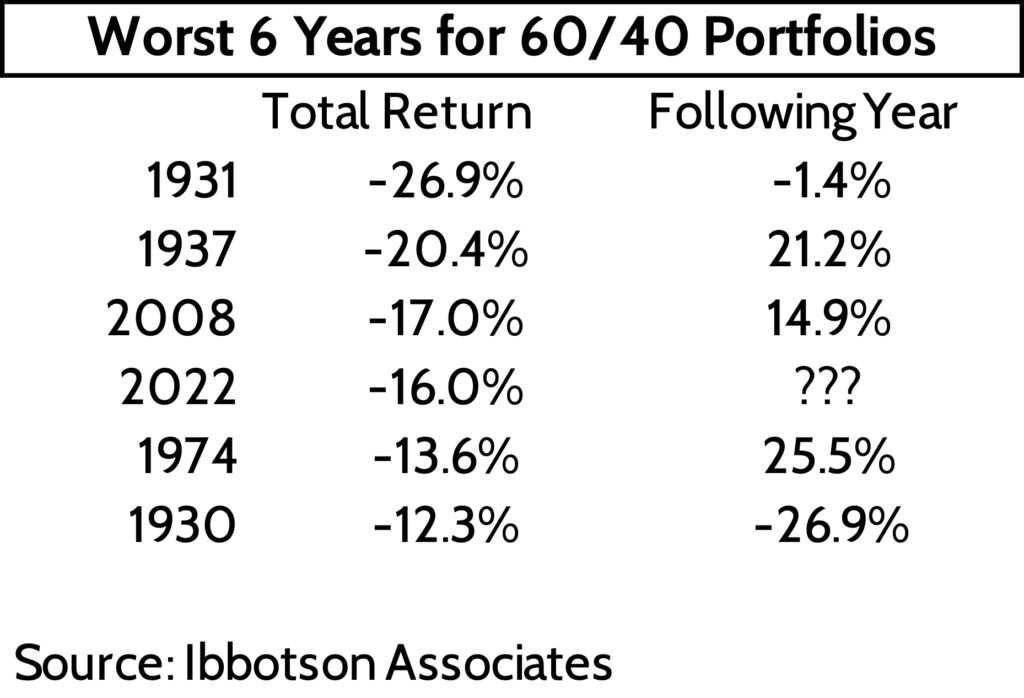

Looking at the difficult 2022 environment differently, we find this year is one of the worst years for the “60/40” Portfolio. This portfolio comprises 60% Stocks and 40% Bonds and is the bedrock allocation of retirees.

If you’re looking for good news in all this, history suggests somewhat better returns after a year like we’re having (putting aside the Great Depression). And going back over the last 20 years, this 60/40 portfolio has generated annual returns of +7.3%, which includes this year and the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Meaning, long-term investors have still done well.

How Investing Will Change in the Next 10 Years

The investment landscape is undergoing a major change. And it’s important for investors to understand why this change is happening, and what it means for the future. I’ll provide more detail on certain aspects of these changes below. But we first have to understand how investors have invested since the late 1990s.

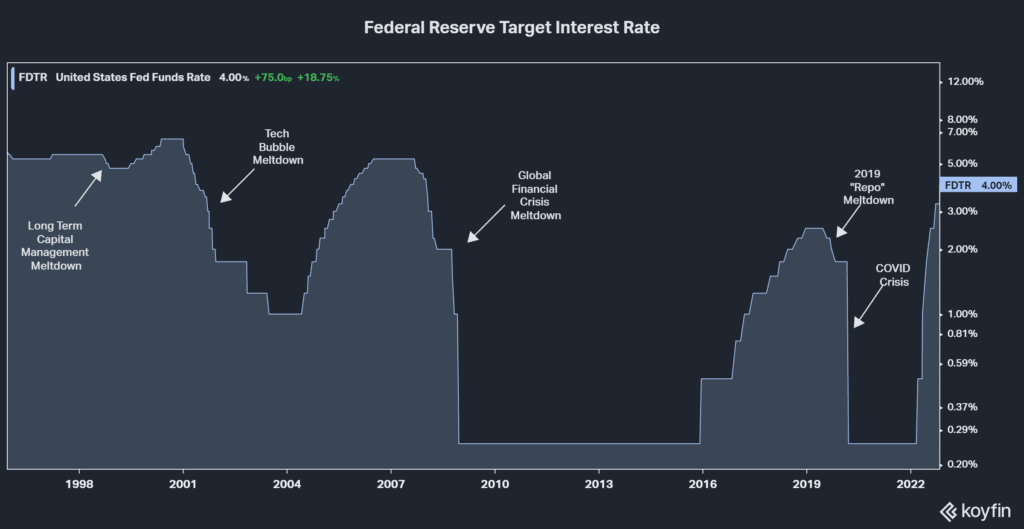

First, investors have placed ultimate faith that central banks – when faced with a crisis – will pull out all the stops to save investors. They have good reason to believe this. The Federal Reserve has repeatedly cut interest rates with every market hiccup, getting more aggressive with their easing each time.

By pushing short-term interest rates to 0% and directly supporting bonds through bond purchases (Quantitative easing), the Fed distorted markets and capital allocation. In human history, it has never been normal for money to be as “free” as it has been the last 20 years. Faced with earning 0% on their savings, they forced investors to put more money in the stock market to get decent returns.

Second, piling into low-cost, passive index funds has become the norm for investors. Let me be clear. Lower investment expenses is a wonderful thing. And passive investing avoids having to gamble on whether or not a fund company will outperform the markets. Passive investing has helped democratize investing, wresting control away from expensive banks and fund managers.

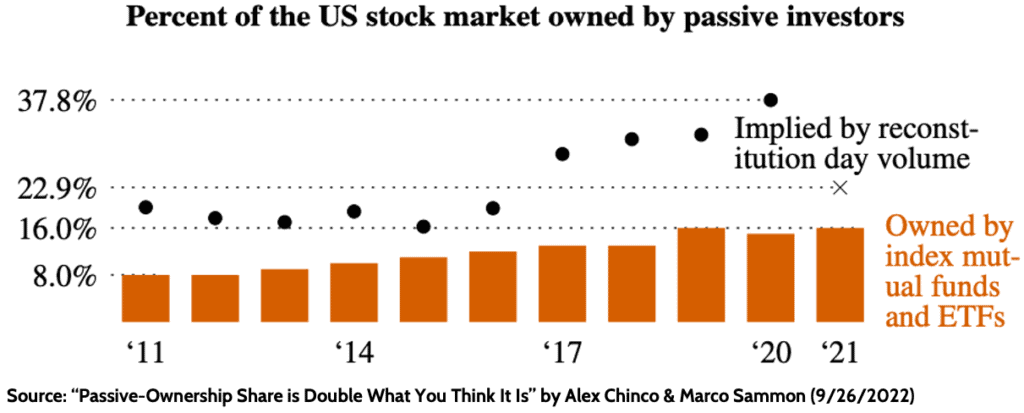

But it’s not all good news. A recent study suggested that upwards of 40% of all investments in the U.S. stock market are passive index funds.

As a greater percentage of the stock market gets tied up in passive strategies, trading liquidity decreases. And decreased market liquidity means sharper moves in the market when economic conditions change. The last 24 months have been Exhibit A of this. We saw stocks fall -35% in March 2020 at the onset of the pandemic, only to rise 120% from the bottom to January 2022.

Additionally, passive index funds aren’t as well-diversified as investors believe. They represent “the market.” As parts of the market become distorted, the passive funds representing these indices also get distorted and less diversified. We see this in the dominance of large tech stocks in the benchmark S&P 500 index, where the Technology sector represents almost 30% of the entire index!

Higher inflation severely challenges these two dynamics. Investors can no longer rely on the Fed to bail them out when stocks go down. If the Fed cuts rates with high inflation, they only encourage more inflation. And 0% interest rates have distorted all types of markets. Passive “buy & hold” investors are facing years of poor returns as those markets – and by definition, those funds – work out the excesses.

We just recorded a podcast episode on this exact topic called, “is buy and hold dead?” If you want to hear more about this topic, take a listen! Find our podcast Behind the Designs on your favorite streaming platform.

What’s Changing: Stocks and Bonds Becoming Correlated

The most obvious – and significant – investment management change in the market is the rising correlation between stocks and bonds. In layman’s terms, a positive correlation means that two things will rise/fall in the same direction. Ice cream sales are positively correlated with rising temperatures. Negative correlations mean that when one thing rises, another thing falls. Sales of boiling hot soup are negatively correlated with rising temperatures.

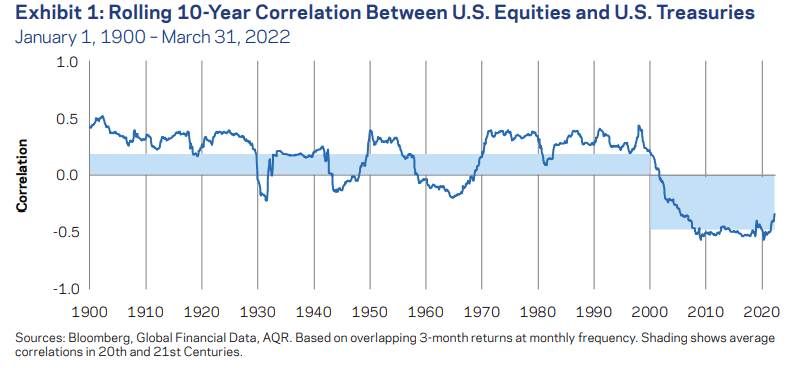

For the last 20 years, we’ve gotten used to stocks and bonds having a negative correlation. This has been most clear during market downturns, such as the post-Tech Bubble period and the Great Financial Crisis. In each of those crises, stocks fell materially but bonds performed well, rising in value as interest rates fell with the Fed cutting rates.

2022 has shattered the illusion of stocks and bonds being negatively correlated. Both stocks AND bonds have performed poorly. Is this a temporary aberration?

The excellent chart above by fund management firm AQR shows stock & bond correlations going back to 1900. What we can clearly see is that the last 20 years of negative correlation between these two asset classes has been a historic aberration. The “norm,” so to speak, has been for stocks and bonds to move in value together.

It’s important to note that the ‘normal’ correlation between stocks and bonds is still low, even if it has been positive. That means there’s still diversification benefits from owning both asset classes through the cycle.

But what this means is that the days of “winning” with a simple “Total Stock Market” fund and “Total Bond Market” fund are over. That worked great when stocks and bonds were negatively correlated. It won’t work so well in the future as correlations return to normal, positive, levels.

The way investors deal with this normalization of correlations is to be as well-diversified as they can get. There are dozens of asset classes underneath the big headings of “stocks” and “bonds.” Investors will have to create portfolios that are more diversified by asset class than they’ve been used to having. And they’ll have to manage those portfolios more actively as different asset classes become cheap or expensive versus other asset classes.

What’s Changing: Higher Interest Rates Reduce Corporate Stock Buybacks

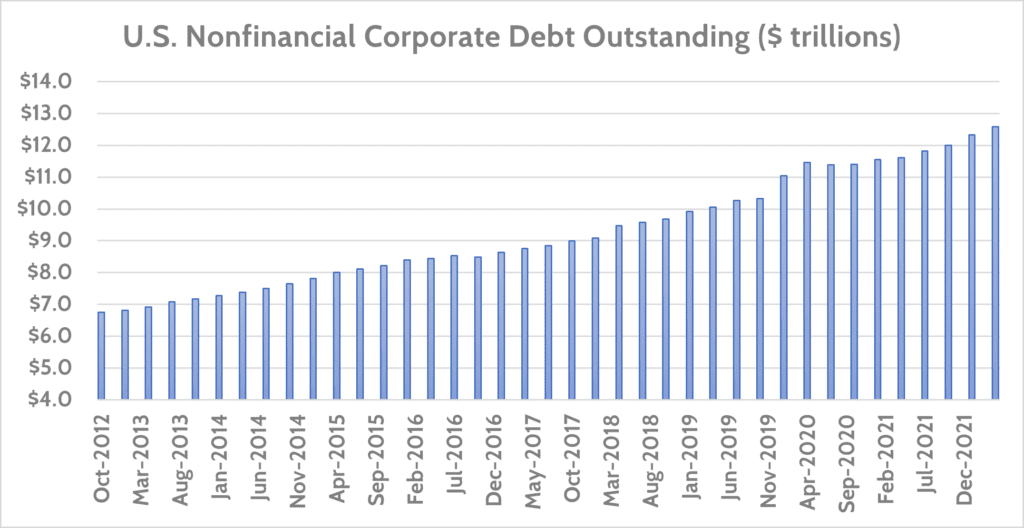

Historically low interest rates have distorted many parts of our society. Companies that normally would have gone bankrupt in recessions were kept alive due to abnormally low borrowing costs. But one of the biggest distortions that low rates wrought was the rise of debt-fueled stock buybacks.

When companies earn a profit, they have a choice how they use those profits. If they’re a growing company, they can recycle profits back into the business to fund new investments and growth. When they’re a slower-growing company, they can increase the dividends they pay to shareholders. Or, they can “return capital to shareholders” by repurchasing their own stock on the open market.

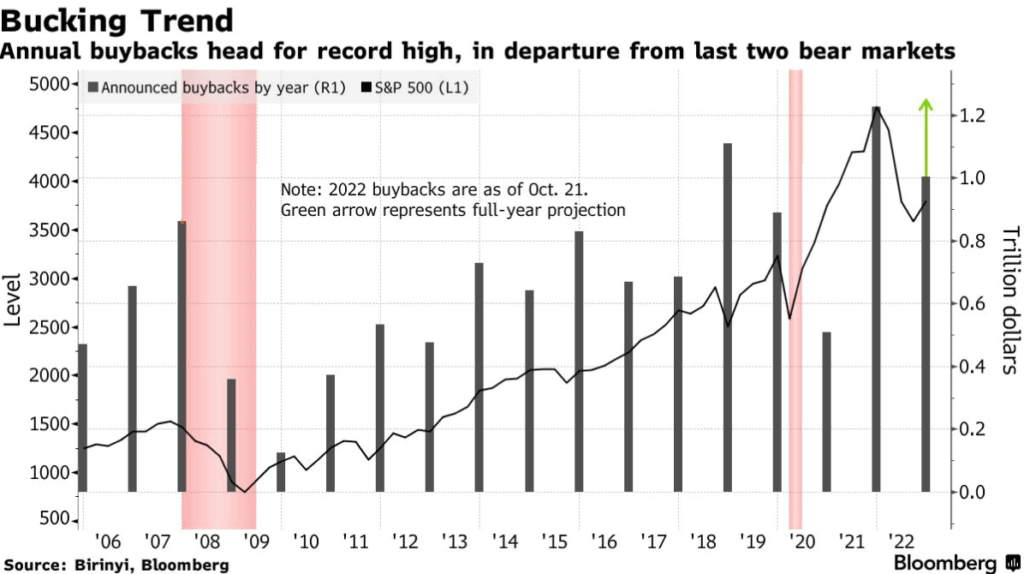

Stock buybacks have been a key support for stocks for the last 10 years, creating a constant “bid” in the market for stocks. For 2022, it’s expected that companies will spend over $1 trillion to buy back their stock, the third time over the last five years that buybacks topped that level.

Buying back stock is a perfectly fine way to create value for shareholders. But the problem is that many companies have engaged in financial engineering to artificially boost their capacity to buy back stocks. They gorged on cheap debt and then used that money to buy back stock.

To put numbers on this, since 2012 companies have increased debt by $5.7 trillion and bought back $8.8 trillion of stock. Not every dollar of new debt has gone to buy back stock. Many companies generate a lot of cash to fund these buybacks. But they wasted a good portion of this debt on non-productive share buybacks whose primary beneficiaries are C-Level management.

As borrowing costs rise, companies cannot engage in this type of financial engineering like they used to. “Rolling over” this debt (i.e. issuing new debt to pay off old debt) will be cost prohibitive. Worse, they face the prospect of having to divert cash flow away from share buybacks in order to pay off debt as it comes due.

The impact of this is that higher interest rates will remove a large buyer of stocks from the market.

What’s Changing: Real, Inflation-adjusted Returns Will Be Lower

The experience of the 1970s taught us that higher inflation makes life difficult for everyone. Lower-income workers without savings see their cost of living diminish. Prices rising on rent, food, and gas eat up a greater proportion of their budget. Higher-income households with lots of savings suffer lower inflation-adjusted returns on their savings and investments.

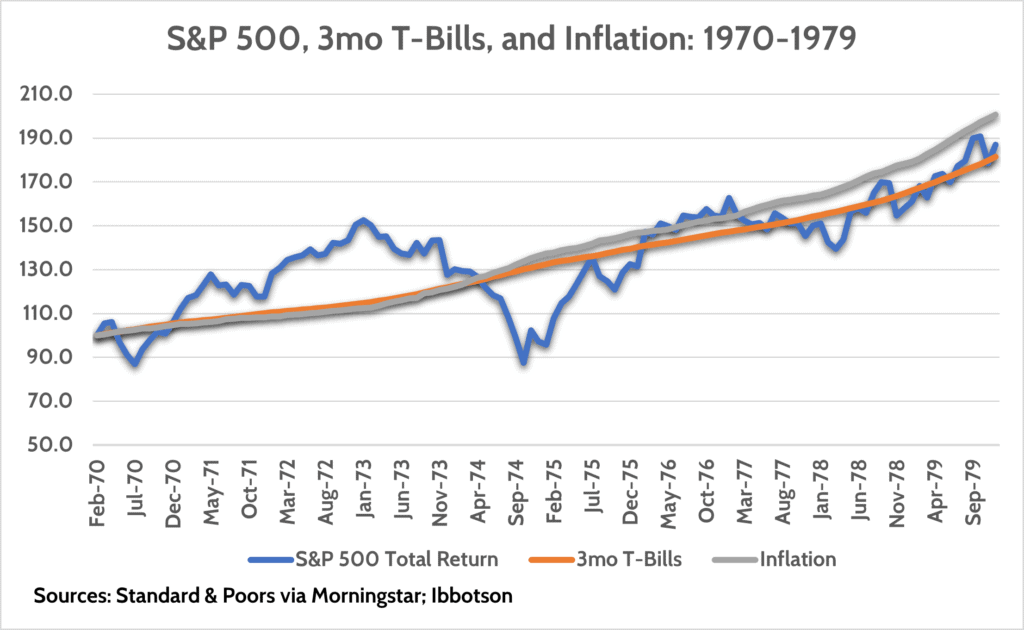

Speaking frankly, the investment experience of the 1970s was poor. Not only did stocks fail to keep up with the pace of inflation, but they also suffered a lot of volatility throughout the decade.

This is the nature of investing for the long-term. We have great decades where investors gain excess returns (80s, 90s, 2010s) and then some “lost” decades like the 70s and 2000s. If inflation proves to be sticky and high in coming years, we may face one of those “lost” decades.

What’s an investor to do? Again, it comes down to investing in many asset classes. There are some non-traditional asset classes such as commodities, real estate, and industrial mining companies. They have exhibited decent performance in inflationary periods.

Probably the biggest change for investors will be seeing good ol’ cash as an asset class once again. We’ve endured 20 years of earning nothing on our savings, but that’s changing. Deposit and money market rates may reach 5% in the next 12 months.

Cash isn’t a good long-term investment as history shows it only keeps up with inflation. Meaning, you earn nothing above the rate of inflation. But in the coming years we see scope to use cash more strategically when managing portfolios. Stocking up on cash in an uncertain market environment and then reinvesting that cash back into markets during downturns.

One thing is clear: Investors have to come to grips with the fact that the “buy & hold” philosophy that worked so well the last 20 years is dead, at least for the next few years. If you’re in your 20s or 30s, you can still take that approach and do well, as your retirement is decades away. But if you’re in your 40s and 50s approaching retirement – or in retirement already – then taking that approach can really hurt your retirement prospects. A “lost decade” in retirement eats up a good chunk of your remaining investment time horizon.

It’s Time to Change Your Approach to Investing

We are facing the most significant shift in the investment landscape since the early 1980s, when high inflation from the 1970s finally fell. Instead, we’re in the early stages of a new, sustained period of higher inflation. The investment strategies that worked so well when inflation was low and the Federal Reserve was accommodative – buy & hold investing, and passive investing – need to be unlearned to be successful in the coming decade.

To achieve investment success over the next 10 years, you’re going to have to be much more engaged with how you’re investing. More investment diversification, more active management of your portfolio, more attention paid towards taxes. Little details are going to add up to a big deal when it comes to generating positive investment returns.

It’s equally important to approach the coming decade with wide eyes. It’s going to be more difficult to make money above the rate of inflation. The days of markets going up double-digits every year – as they’ve done over the last 10 years – are over.

If you want to learn more about the investment management changes, head over to our podcast to hear more! Be sure to take a listen!

The most important thing you can do is to engage with a firm like Financial Design Studio to manage your investments. We live and breathe portfolio management every day. Watching market trends, investing clients in well-diversified portfolios, all while keeping a close eye on taxes. It takes a lot of work, but that’s what we’re paid to do.

The ongoing financial planning we do for our investment management clients also adds value to your financial life. We help you identify goals and then put real math behind them so you can be confident in the goals you can achieve. Is it time to reach out and see how we can help you?

Ready to take the next step?

Schedule a quick call with our financial advisors.

Recommended Reading

Target Date Funds Explained! [Video]

In this video, target date funds are explained, we share the pros and cons of using this strategy, and how age based funds work.

Why We Invest In Stocks, Bonds, and Cash [Video]

In this video we break down why our investment management focuses on asset allocations of stocks, bonds, and cash.

Rob Stoll, CFP®, CFA Financial Advisor & Chief Financial Officer

Rob has over 20 years of experience in the financial services industry. Prior to joining Financial Design Studio in Deer Park, he spent nearly 20 years as an investment analyst serving large institutional clients, such as pension funds and endowments. He had also started his own financial planning firm in Barrington which was eventually merged into FDS.